Matthew Mondschein

"A few weeks ago, I found myself at a protest of hundreds of people marching down Las Vegas Boulevard, past the sleek hotel-casinos, while the demonstrators sang and yelled chants demanding for a ceasefire in Gaza. Armed with my Nikon F3 loaded with some Tri-X, and my GH5, I sneaked through the crowd, climbed on ledges, all to get at least one frame that I’d be proud of."

Matthew Mondschein

Praxis in Sin City

by Matthew Mondschein

Featuring excerpts from Vladimir Mayakovsky’s “Our March”

“Beat the squares with the tramp of rebels!

Higher, rangers of haughty heads!

We’ll wash the world with a second deluge,

Now’s the hour whose coming it dreads.

Too slow, the wagon of years,

The oxen of days — too glum.

Our god is the god of speed,

Our heart — our battle drum.

Is there a gold diviner than ours/

What wasp of a bullet us can sting?

Songs are our weapons, our power of powers,

Our gold — our voices — just hear us sing!

Meadow, lie green on the earth!

With silk our days for us line!

Rainbow, give color and girth

To the fleet-foot steeds of time.

The heavens grudge us their starry glamour.

Bah! Without it our songs can thrive.

Hey there, Ursus Major, clamour

For us to be taken to heaven alive!

Sing, of delight drink deep,

Drain spring by cups, not by thimbles.

Heart step up your beat!

Our breasts be the brass of cymbals.”

Megapixels and Mayakovsky

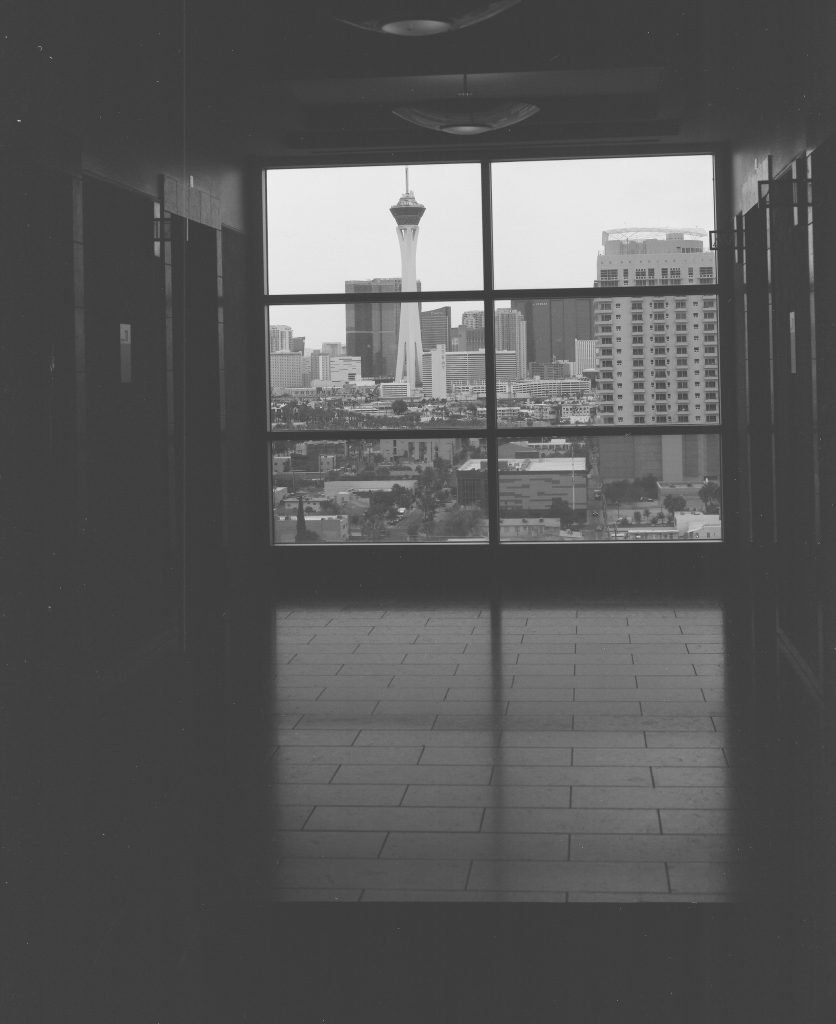

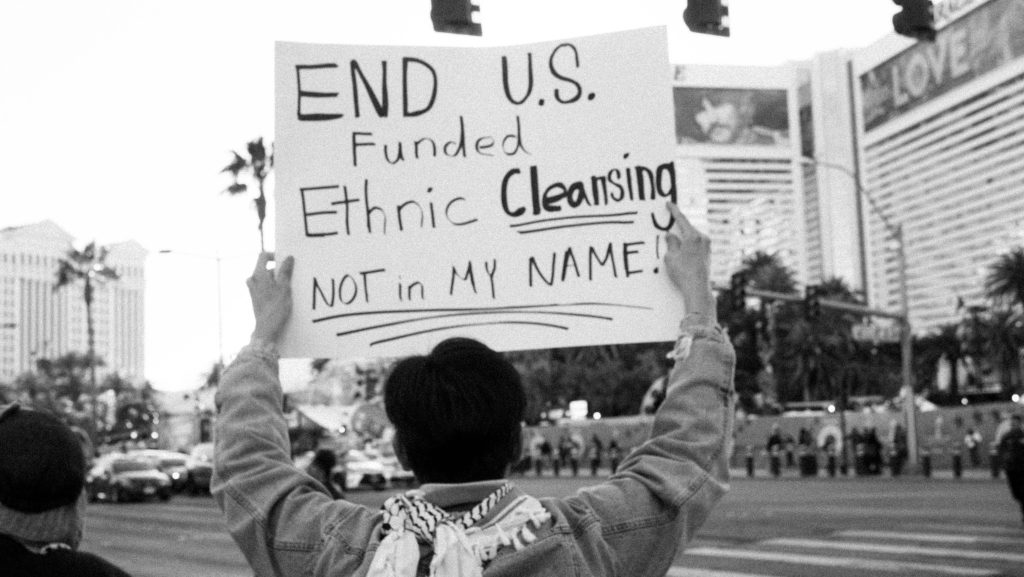

A few weeks ago, I found myself at a protest of hundreds of people marching down Las Vegas Boulevard, past the sleek hotel-casinos, while the demonstrators sang and yelled chants demanding for a ceasefire in Gaza. Armed with my Nikon F3 loaded with some Tri-X, and my GH5, I sneaked through the crowd, climbed on ledges, all to get at least one frame that I’d be proud of. As the protestors filled the narrow walkways of the Vegas Strip, liquored up tourists moved to the side, pulling out their phones to take photos and videos. Seeing this angered me, reducing what the protestors were doing to some sort of individual spectacle. Yet, there I stood, angry at these tourists for snapping photos and taking videos with smiles on their faces, while I had two cameras strapped on each shoulder.

How am I any different from these people? I thought, because the sensor in my camera is bigger than the one in their phone? Do more megapixels mean I’m a documentary photographer and they are not?

Why am I even taking photos?

After all, I’ve always considered myself a writer. In elementary school, I wrote stories for classmates in a notebook and slid it in between folded construction paper to use as a cover. After a while, more and more classmates wanted their own copies, so I had to rewrite the story by hand, but I guess reprints are good news for a writer, even if the stories were nonsense written by a 10-year-old.

Photography is something that I picked up only a few years ago. After being discharged from the Navy, and with a new sense of freedom and loneliness, I needed something to do. So I bought a Pentax K1000 on the recommendation from a friend without knowing how to load film, what ISO or the exposure triangle meant, for that matter. But I learned, out in the streets, and soon one roll with only one decent frame became a roll with a couple more decent frames that I was happy with. Then came learning to develop my film, and teaching myself basic editing, and that was that. Photography, to me, is observant. It can create an alternative perspective of reality or subject. It allowed me to view the world where the smallest detail can contain a universal beauty that elicits emotion. It allowed me to view life where every detail, to the smallest degree, can be sacred.

So much of our modern life is image based. I have distinct memories watching the War on Terror play out in front of me on television when I was young. Men and women with cameras, with various frames per second, document these events so a young boy like me can watch all the way in Las Vegas, safe in a suburban home. Yet by the time I was in high school, names of war correspondents and photojournalists like Marie Colvin and Tim Hetherington were like idols to me. They were people who put themselves into dangerous situations to show what the reality of life was for people living in war or violence. And some, like both Colvin and Hetherington, died while doing so.

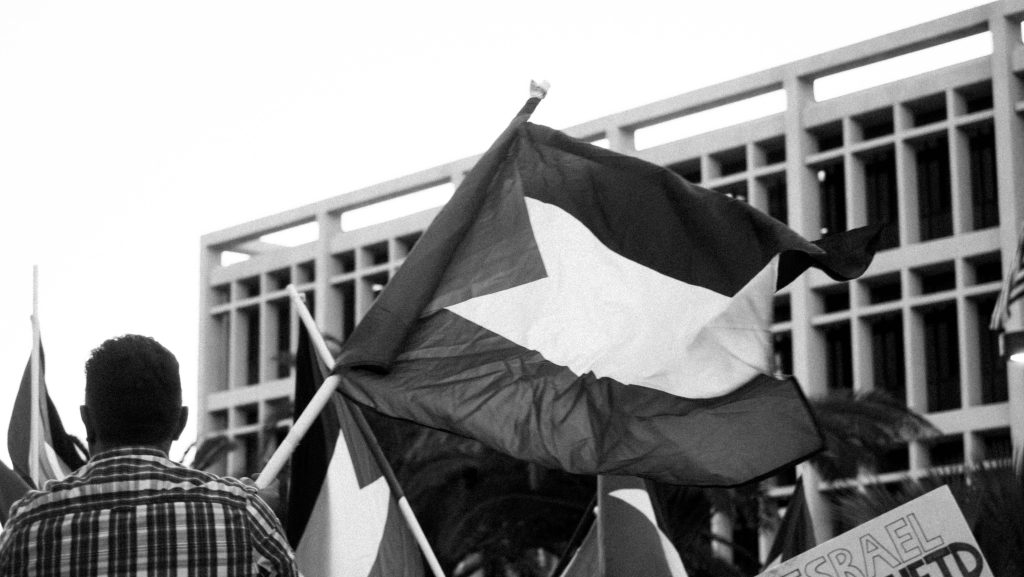

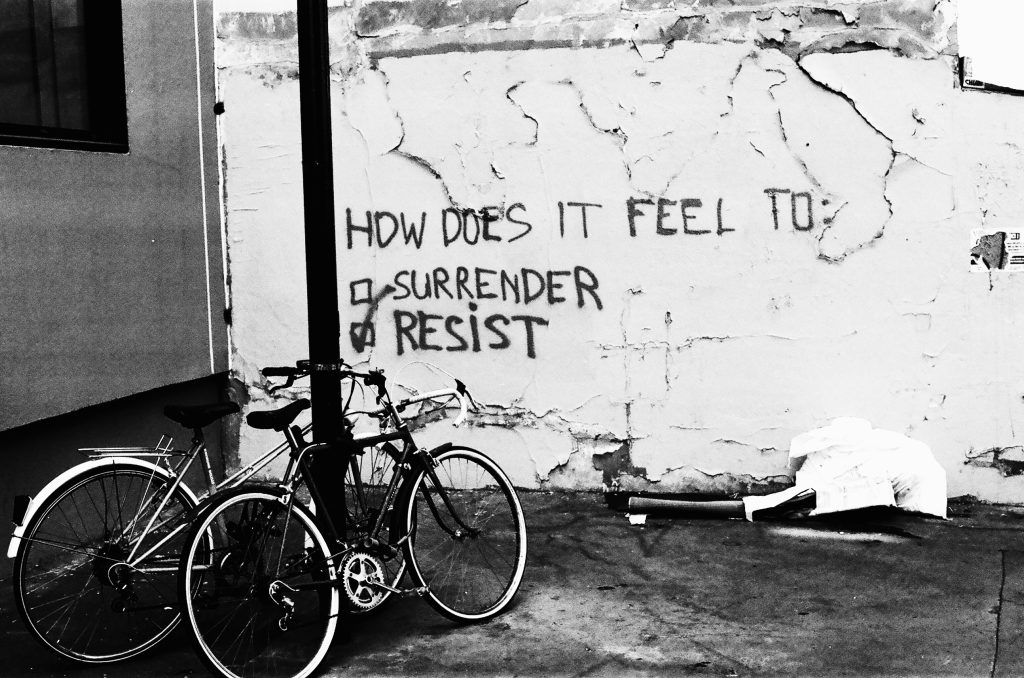

By high school, I was reading revolutionary books and theory (though not comprehending much of it). But it felt good to read, as if I wasn’t alone, knowing that people had felt how I felt for a long time. Somehow synthesizing my political activism and my love for photography became a goal of mine, and soon I found myself at protests, speaking to and befriending organizers, and snapping photos. And for a while, it felt like my project of bridging the two was working. I shot anti-war protests, protests against the overturning of Roe vs Wade, rallies for indigenous rights, marches calling for a ceasefire in Gaza. I was out in the streets, talking to people, and documenting these events in my own way, the best that I knew how.

Yet all it took was looking into the lens of an iPhone camera, held by a laughing, middle aged drunkard, for me to question the intention behind my own photographs. Was I documenting this activism — an effort to change the world — or was I just creating a spectacle meant for clicks and social media engagement? Has activism, in a way, become something to drive social media engagement? Snapping the one photo that would make my name as a photographer?

For the rest of that protest, I didn’t take a single photo; my cameras just swung from my shoulders.

What is the role of art and journalism in political organizing spaces, be it writing, painting, or photography? I wasn’t sure, but I felt lost. I left my cameras at home the next few marches and protests because I thought that they were not needed there — my voice and a bullhorn was. There needed to be a separation between activist and journalist, a separation between observer and subject. Weeks later, I was at a bookstore where I found a collection of poetry written by someone that I read years before, Vladimir Mayakovsky. A staunch socialist and Bolshevik radical from an early age, he was arrested in 1909 for smuggling women political activists out of prison and given an 11-month sentence. It was in solitary confinement that he started to write his first lines of poetry. “Revolution and poetry got entangled in my head and became one,” he wrote about his time in prison. When released, he was disillusioned with himself as a revolutionary, and instead began to focus on education and art, attending the Moscow Art School.

Yet by the time the October Revolution came in 1917, and then the Russian Civil War, Mayakovsky became a leading figure and spokesperson for the revolution, reading his poetry to masses of workers, telling the story of the revolutionaries through verse. He used his artistic prowess to fuel the revolution, and the revolution fueled his poetry to think in abstract ways, to challenge tradition as one of the leading Futurist Soviet poets.

From Mayakovsky, I came across John Reed’s book 10 Days That Shook The World. Reed, an American journalist and socialist, was in Russia during the October Revolution, covering meetings in the worker Soviets and factories, detailing the armed uprising of the Red Guards, and reporting on meetings and speeches from Lenin and Trotsky to leaders of the opposition party. In his preface, Reed explicitly says that, while covering the events of the October Revolution, his “sympathies were not neutral. But in telling the story of those great days I have tried to see events with the eye of a conscientious reporter, interested in setting down the truth.”

Was Mayakovsky any less of an artist for the side and role he took in revolution? Was Reed any less of a journalist since he was a declared socialist? Can journalists even exist outside of ideology? The answer, according to philosopher Slavoj Zizek, is no: “It’s exactly when we think we exist outside ideology that we are actually the most in it.”

After weeks of my cameras literally collecting dust on the shelf, I decided to bring them back out to the next protest that I wanted to document, an emergency “Hands Off Rafah” rally that took place here and throughout the country for Palestinians under siege in Gaza. The protestors marched under the Fremont Street canopy. Crowds of onlookers looked confused that these demonstrators were protesting in their zone of fun. And I was there, with my camera, trying to take photos that can stay loyal to the truth of the event. I figured, like Reed, that my sympathies could be “partisan,” but I could do my best to be a reporter interested in setting down the truth.

Through a photo, we get a glimpse of a moment — a moment of love, of rage, of quiet intimacy, of history. So when I take my camera out to document a protest or a meeting of comrades or my city and the people that live in it, I’ll keep in my mind, behind every frame: What kind of story am I trying to tell? How can I be intentional about each photo I take? Hopefully, one day I will be able to synthesize my art and politics like Mayakovsky, or find myself swept up in a historical event that changed history like Reed. And one day, I hope, I’ll make an impact like they did.

“The drum of war thunders and thunders.

It calls: thrust iron into the living.

From every country

slave after slave

are thrown onto bayonet steel.

For the sake of what?

The earth shivers

hungry

and stripped.

Mankind is vapourised in a blood bath

only so

someone

somewhere

can get hold of Albania.

Human gangs bound in malice,

blow after blow strikes the world

only for

someone’s vessels

to pass without charge

through the Bosporus.

Soon

the world

won’t have a rib intact.

And its soul will be pulled out.

And trampled down

only for someone,

to lay

their hands on

Mesopotamia.

Why does

a boot

crush the Earth — fissured and rough?

What is above the battles’ sky –

Freedom?

God?

Money!

When will you stand to your full height,

you,

giving them your life?

When will you hurl a question to their faces:

Why are we fighting?”

EXPLORE MORE STORIES

Latisha Boyd

Eduardo Rossal

Miriam Aydoun